Sabbath rest, not recharge

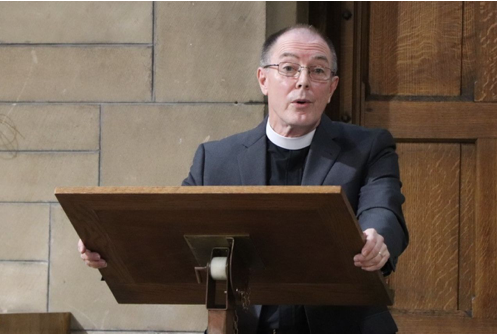

The Reverend Dr Michael Hull writes:

The sabbath rest is unique to Judeo-Christianity. To a certain extent so too are our holidays when rightly understood. We do not rest in order to recharge, as it were. We rest to enjoy God’s gratuitous generosity. Rest is an end in itself.

The Book of Genesis provides a matchless account of creation wherein God speaks and the universe as we know it comes into being and order, wherein humanity is made in God’s image and likeness, and wherein the account incorporates rest into creation (Genesis 1 and 2). God fashions and blesses his creation, and he pronounces it good, still the account uses one word solely for the sabbath: the seventh day is ‘hallowed’ or ‘consecrated’ (Hebrew: qādash). The grand finale of work is rest, not more work. The sabbath is for rest, not for revitalising for more exertion. The sabbath is an end in itself.

Genesis 3 goes on to present a picture of our preternatural state that precludes output. God has done all the work and placed us in the Garden of Eden where we are in a state of rest. All is well, and God walks with us, until we sin. Cast out of the Garden, it would seem that rest of any sort is a lost luxury, yet rest is a gift God does not retract. God neither revokes his fashioning nor his blessing nor the sabbath rest at the Fall. He incorporates, instead, the gift of rest into the Ten Commandments. Exodus 20.7–11 specifically reminds us of the hallowing of the sabbath in Genesis. And Deuteronomy 5.12–15 equates inability to consecrate the sabbath with the Hebrews’ bondage in Egypt. One who cannot rest is a slave. But again, the rest spoken of in Exodus and Deuteronomy, as in Genesis, is not for any purpose other than God’s scheme for us. Our humanity is not ordered to productivity. We are most ourselves when we are free to rest in God.

Sabbath rest, though, is often confused with recharging: as if the value of rest is found in enabling productivity, as if human labour and its products are our purpose. Ideologies that, like atheistic communism or laissez-faire capitalism, value refreshment only insofar as it enhances yield denigrate humanity. We are made in the image and likeness or God and, furthermore, redeemed in Jesus Christ. It is counter-intuitive to us in our fallen state to know, as the Psalmist reminds us, we are ‘fearfully and wonderfully made’ as ends in ourselves (139.14–16). We were not created and redeemed for an earthly end but for a heavenly one. Sabbath rest is a temporal foretaste of the beatific vision wherein we shall enjoy God for eternity. So important is this insight, and so easily missed, that God includes it in the Decalogue. God does not order us to work. God orders us to rest. To keep the sabbath is to fix our eyes on God rather than things, even good things. It is to dwell now, as least partly, in the new Jerusalem of Revelation 21.

One day a week is set off for rest in God wherein we worship and enjoy leisure, and every holiday is best cast in the mould of the sabbath vis-à-vis our freedom and Redemption. It behoves us to keep this in mind as we plan and relish our holidays. Holidays, akin to the sabbath, are best when they are allied to our ultimate end in God’s fulness and peace. Misunderstandings of industry would suggest that our holidays are worthwhile when they recharge us to produce or renew us for this-worldly tasks. Nothing could be farther from the truth or more ignorant of God’s design. Our misguided fascination with fabricating as if we could build a city of God on earth by the sweat of our brow results in frustration akin to the Tower of Babel (Genesis 11.1–9). God has a different blueprint for our lives here on earth and hereafter in heaven. Jesus picks up on Isaiah’s words (28.12) when he says, ‘Come to me, all you that are weary and are carrying heavy burdens, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you, and learn from me; for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light’ (Matthew 11.28–30).

The gift of sabbath rest is not only for Sundays. It is a gift that allows us to turn our holidays into holy days, wherein we hallow and consecrate them to God. To rest and to enjoy God’s gratuitous generosity is its own reward in this world and our definitive end in the world to come.