St John the Baptist and prophetic witness

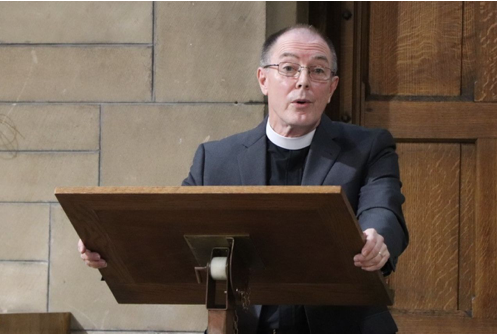

The Reverend Dr Michael Hull writes:

The Church commemorates the Beheading of St John the Baptist annually on 29 August. It is an odd feast. John is not a Christian martyr insofar as martyrdom has to do with dying on behalf of the faith. Still this feast has been kept by Christians since at least the early fifth century. The price for John’s prophetic witness in the first century was high. It remains high these many centuries later. John’s testimony to the truth meant jailtime and martyrdom.

John bursts onto the scene in Palestine around AD 26 proclaiming the need for repentance and finds himself imprisoned and beheaded around 31 for reproving Herod Antipas’s adultery and other evils (see Luke 3.1–20). The Gospels describe him as a prophetic figure. He is dressed in camel’s hair and a leather girdle (Matthew 3.4; Mark 1.6; cf. 2 Kings 1.8). John is like one of the Old Testament prophets. He is called ‘Elijah who is to come’ by Jesus himself, who also says that ‘among those born of women there has arisen no one greater than John the Baptist’ (Matthew 11.11–15).

John was virtuous and honest. One example is given in Matthew’s Gospel. John has been baptising hundreds, perhaps thousands, with a call to repentance and the words of Isaiah 40.3 on his lips: ‘Prepare ye the way of the Lord! Make straight his paths!’ John, presumably, has been baptising without distinction, yet he has a visceral reaction to some Pharisees and Sadducees who come to him. He calls them a ‘brood of vipers’ (Matthew 3.1–10; cf. Luke 3.1–10). Note that Jesus will later call Herod ‘that fox’ (Luke 13.32). Another example is found outwith the Gospels. The Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, a onetime Pharisee himself, reports that Herod knew John to be a good man who was popular with the people because of his righteousness and piety. Josephus tells us that Herod feared John’s integrity and influence. Herod jailed and killed John to silence him on account of John’s demand that Herod repent of his shameful personal life (Antiquities of the Jews 18.5.2).

The Gospels depict the watershed moment for John at one of Herod’s birthday parties (Matthew 14.1–12 and Mark 6.14–29). Herod was so pleased by Salome’s dance that he rashly promised her almost anything. Prompted by her mother, Herodias, Salome asked for John’s head. Misogynistic readings of the story tend to lay the blame on Salome and Herodias, but it was Herod who delivered the head on a platter. Herod, we are told, feared opprobrium, not Herodias or Salome. He did not want to be embarrassed in front of his (male) guests. Who were they? Many were courtiers (politicians, soldiers, officials of one stripe or another), and it is likely that the guests included recognisably religious people in good number: Pharisees, Sadducees, Herodians and scribes, to name a few, the same folk who gave Jesus such a hard time later on. St Mark tells us that Pharisees and Herodians conspired to destroy Jesus (3.6; cf. 8.15) and that, in turn, they tried to trick Jesus on tribute to Rome as did the Sadducees on resurrection and the scribes on the Commandments (12.13–34; cf. Matthew 22.15–40 and Luke 20). History records no voice of theirs against lopping off the head of John, the true prophet in their midst. They may well have been, as John had prophesied, a brood of vipers, or perhaps just frightened sheep who feared ‘that fox’ rather than God.

The whole scene should give those of us who espouse the Christian religion great pause. We need to ask ourselves if, in our ecclesiastical readings thereof, we eschew laying blame on Herod or his guests to countenance our silence and complicity with evil today. Faux morality gives the tetrarch a pass whilst demonising lesser powers and overlooking tacit consent. That is not to assuage Salome’s or Herodias’s culpability, however it is to say that John’s blood is on the potentate’s hands, and the guests at this dreadful dinner party are guilty as well of viperous complicity or sheepish silence or both to some measure. Thankfully, our forebears in the faith sensed the potential for negligence of the truth and the flagging of prophetic witness by God’s people. They kept the feast of the Beheading of St John the Baptist from the earliest days of the primitive Church as testimony to the fact that prophetic witness to the truth may mean jailtime or martyrdom. Let the feast we keep inspire us to speak forthrightly on behalf of truth and to act decisively against evil. The stakes are high, for otherwise we risk an eternity of Herodesque parties rather than the heavenly banquet with the Baptist and those washed in the blood of the Lamb (Revelation 7.14).