The Cup of blessing

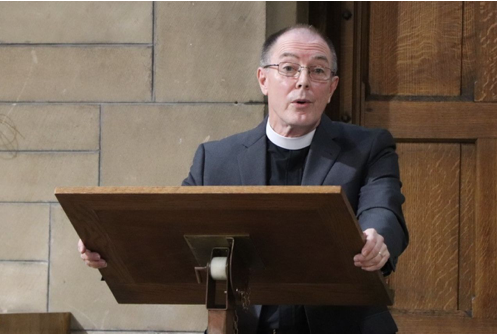

The Reverend Dr Michael Hull writes:

September 2022 marks the return to the common cup to my local church. Among the many deprivations of the Covid-19 pandemic and its aftermath has been the loss of the consecrated wine for the last two- and one-half years. Its return is a cause of rejoicing insofar as the risk of contagion is waning and, much more importantly, a palpable aide-mémoire of the gift of the Holy Eucharist. Yes, there were a plethora of substitutes for communal prayer when we were unable to gather in common. Yes, the provision of taking the consecrated bread alone in our contagious times afforded us the whole of Christ in the Sacrament of Holy Communion, for he cannot be divided. Yet, Holy Scripture is clear: the ideal of the Sacrament requires common participation in the one loaf and the one cup.

St Paul of Tarsus, writing in the mid-50s to the church he had planted in Corinth, took umbrage at the Corinthians’ disunity and their irreverence at the Eucharist (1 Corinthians 11.17–33). To focus their attention on the harmony of the Sacrament, he asks them, ‘Is not the cup of blessing for which we give thanks a participation in the blood of Christ? And is not the bread that we break a participation in the body of Christ?’ (1 Corinthians 10.16). The cup, which Paul puts first here, and the bread, effect what they signify, namely a community gathered to feast at the holy table according to the Lord’s ordinance and commandment at the Last Supper: ‘do this in memory of me’ (1 Corinthians 11.24; Luke 22.19; cf. Exodus 12.14).

The pandemic and its aftermath ruptured our unity when we could not gather in church, and it ruptured our celebration of the Eucharist when we could not participate with the one loaf and the one cup, as is willed by God for partaking of the Sacrament. It may seem that the loss of the wine is inconsequential when we are able to receive the bread. Do not other Christian communities, like the Roman Catholic Church, celebrate their Eucharists ordinarily with the bread alone for the laity? Yes, they do, but the reception of the consecrated bread and wine by all participants at Holy Communion has been a staple of Reformed Christianity in Britain for over five centuries. Receiving both elements is a luxury borne of the necessity of Christ’s injunction to do just that.

Moreover, the Greek word translated into English as ‘cup’, potērion, as used by Jesus, underscores its consequence. It may connote a mundane drinking vessel (Matthew 3.25; Mark 7.4; Luke 11.39). It also may connote his sufferings (Matthew 20.22, 23; 26.39, 42; Mark 10.38, 39; 14.36; Luke 22.42; cf. Revelation 14.10; 16.19; 18.6; Psalm 11.6; Isaiah 51.17, 22). In the Gospel of John, after Judas has betrayed Jesus with a kiss, Simon Peter reacts violently by drawing his sword and attacking Malchus, the high priest’s servant. Jesus rebukes him saying, ‘Put your sword into its sheath; shall I not drink the cup that the Father has given me?’ (18.1–11). The ‘cup’, then, when Jesus uses it at Last Supper, connotes both the vessel and his sufferings. The context is significant. The new covenant is in his blood (Matthew 26.28; Mark 14.24; Luke 22.20; cf. Exodus 24.8; Jeremiah 31.31). The absence of the common cup at the Eucharist is a deprivation indeed.

We ought to rejoice heartily on having the cup of blessing back, as well as on this post-pandemic opportunity to reflect on the gift of the Eucharist, particularly on the incarnational reality of its ancient inception and present celebration. By God’s will and grace, we are incarnate spirits, not disembodied ghouls. In the Incarnation, that is in Christ’s enfleshment, the Second Person of the Holy Trinity becomes like us in all things save sin (Hebrews 4.15) and dwells among us (John 1.14). The unnatural isolation experienced in the recent past and the iniquitous tendency in our day to fancy transcending the limits of our own enfleshment by technical advances belie the Christian sacramental life. By the means of a material thing like water, we become living members of Christ’s Church. By the means of bread and wine, we are regularly fed with the Body and Blood of Christ, ‘to the end that all who shall receive the same may be sanctified both in body and soul, and preserved unto everlasting life’ (‘Prayer of Consecration’, Scottish Liturgy).

The Blood of Christ is, to be sure, no small thing for us. St Peter’s words are worth recalling at the return of the cup of blessing: We rejoice in this! Though we have been grieved by trials, we pray that the result is praise and glory and honour at the revelation of Jesus Christ (1 Peter 1.6–7).

The Reverend Dr Michael Hull has been an Assistant Priest at St Vincent’s since 2015. He is also Director of Studies for the Scottish Episcopal Institute.